Carbon and oxygen isotope analysis of carbonates and the development of new reference materials

Carbon and oxygen isotopes in carbonate are a useful tool that can tell us about our environment. For example, oxygen isotopes in tooth enamel are useful in archaeology when researchers want to find out where individuals they are working on are from, or to track animal movement and husbandry. We can also use this technique to analyse modern-day shells of molluscs such as whelks or scallops, to see how they are adapting to rising sea-water temperatures as a result of climate change.

Stable isotope analysis at BGS

The Stable Isotope Facility at BGS can analyse a range of carbonate types, including tooth enamel, speleothems, calcite minerals and a wide range of shells, for carbon and oxygen isotopes. We currently have several instruments that can analyse carbonate materials including very small samples down to 5 micrograms — which would fit on the head of a pin!

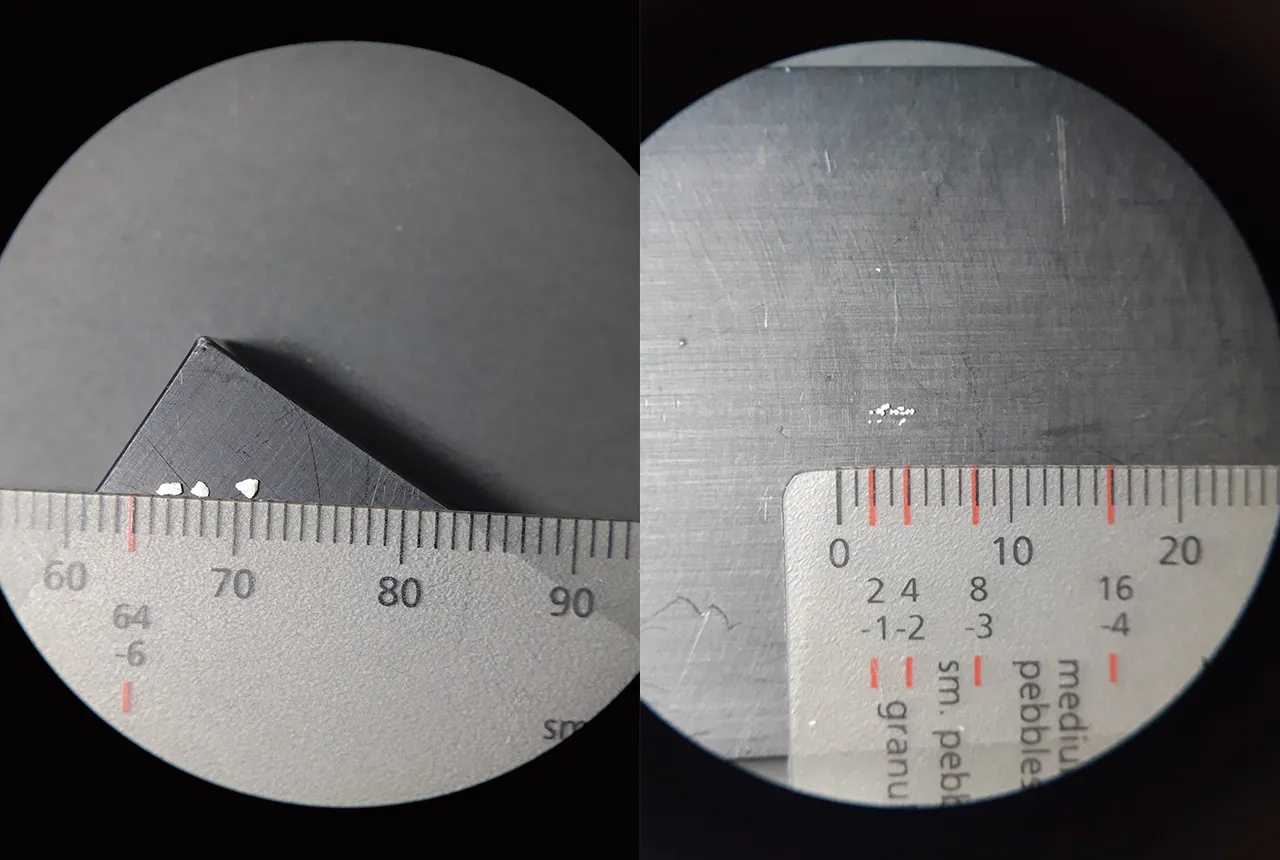

Two examples of the type of grain–size standard we use in our analyses. The measurements are in 10mm increments. BGS © UKRI.

During analysis, laboratory staff need to check whether the sample data produced is accurate. We do this by analysing standard materials that have a predetermined value in every sample batch. Both the samples and standards are analysed using the same method, so if the standard data is accurate and precise, the sample data should be correct. Standards are also used to correct data if there is a measurement offset from the known value. We use multiple standards to cover the range of our sample isotopic values.

Why do we need in-house standards?

We are developing new in-house (internal) standards to use in our laboratory for three reasons. Firstly, we analyse thousands of samples each year, which means we need a lot of standard material. International standards provided by external bodies can be expensive and can run out, so creating our own standards internally helps decrease costs and makes sure there’s always enough standard material available.

Secondly, because we analyse some unusual carbonates, it is best to have a standard that matches the sample material we are measuring. Finally, there are very few oxygen isotope standards currently available for carbonates, especially carbonate in tooth enamel. This is because carbonates in powder form exchange oxygen with the atmosphere, causing carbonate isotope values to change over time, meaning materials used for standards do not last long.

What are we testing?

We are currently working on developing three new internal carbonate standards that we can use as a reference material for our work.

The first is Bahamian oolite aragonite, which we call BOA for short, which comes from a beach composed of oolitic sand in the Bahamas. BOA is composed of round and tiny, egg-shaped ‘ooids’, which form in warm shallow seas and are then deposited on the beach.

Bahamian oolite aragonite (BOA). BGS © UKRI.

The second is made up of fragments of whelk shells, (sometimes known as sea snails). The shells we have are waste from the fishing industry, where the whelk is removed and sold as food and the shells are repurposed for decorative use and in gardening.

The third and final material is from a high-temperature skarn (HiTS) rock that has come from western Romania. This rock formed when magma heated limestone bedrock from below, producing a skarn punctuated with calcite veins, which we extracted. This material is probably the most valuable to us as it has a very low oxygen isotope composition, making it useful as a reference material for archaeological tooth enamel samples, as they tend to have low values.

Creating the internal standard

To use these new materials as an internal standard, we need to ensure that they meet certain requirements:

- they have homogenous carbon and oxygen isotope values

- there is an isotopic and chemical match to routine samples

- they are affordable, available, accessible and abundant

- they are chemically and isotopically stable over time

To make sure we meet these requirements, we have been working with other teams within BGS to help characterise our materials. So far, we have analysed them using our scanning electron microscope and X-ray diffraction, which tell us about what elements make up these materials to check for impurities.

We are currently analysing our three new standards at the Stable Isotope Facility over an extended period of time, to ensure that they produce consistent isotope values. So far, we have values with an error of less than 0.2 per mil, which is great news for the possibility of the Stable Isotope Facility’s laboratories and others in the organisation using these materials as an internal standard in future carbonate research. We hope to make these new standard materials available to other stable isotope facilities soon!

Contact

Please get in touch with either of the authors if you are interested in participating in an interlaboratory comparison, to enable us to certify the values of these new standard materials.

About the authors

Kotryna Savickaite

Geochemistry technician

Dr Charlotte Hipkiss

Stable isotope research assistant